Why TypeScript is Essential for Developing Large-Scale Frontend Projects

Introduction

How can I blame you for making mistakes, when I gave you too much freedom. -- Jacky Cheung "Too Much"

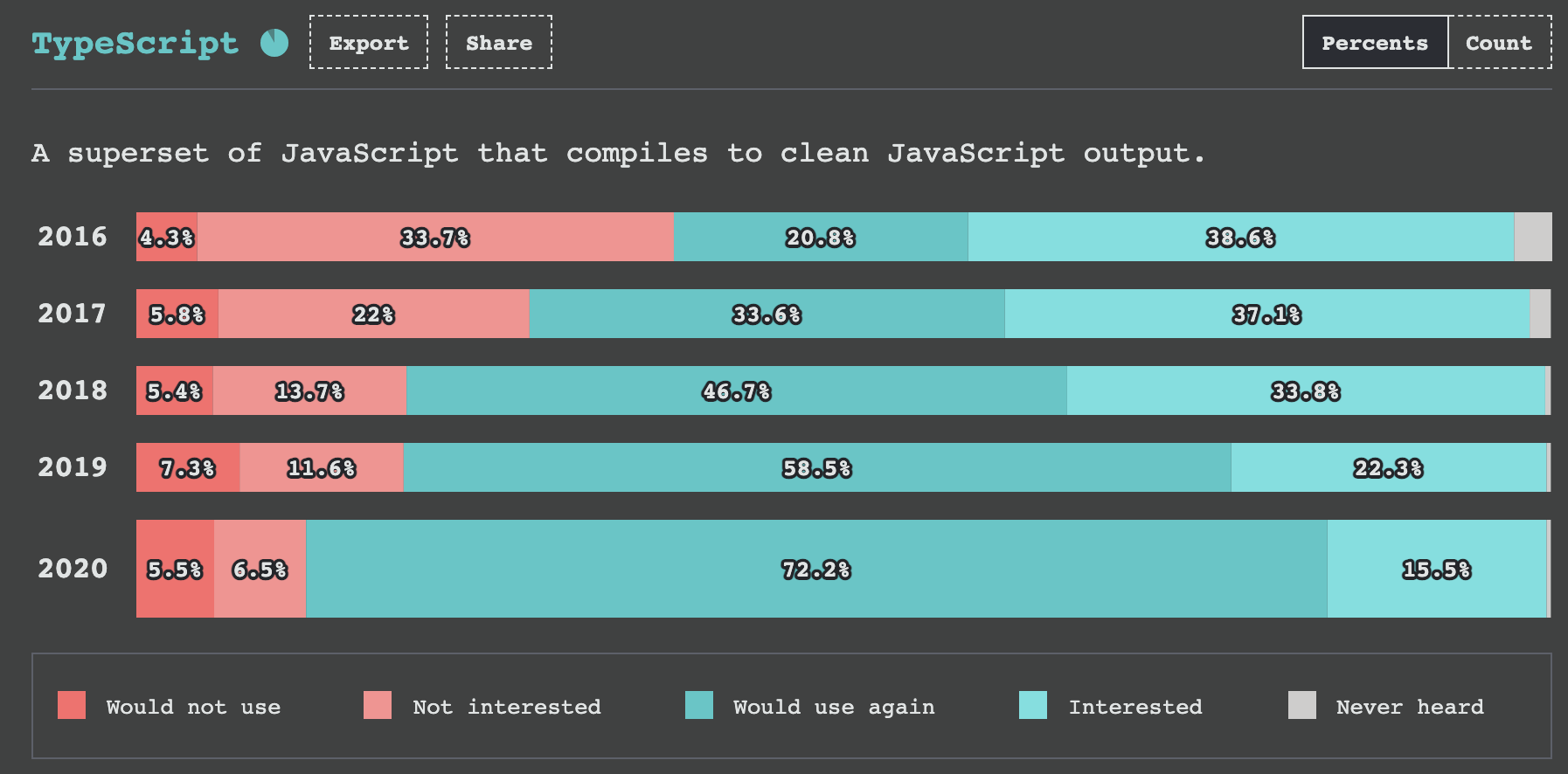

Many software engineers probably know or understand TypeScript (abbreviated as TS) to some extent, and frontend developers who have used TypeScript consistently express positive feelings about it. If you search for TypeScript on search engines, you'll find an overwhelming number of articles praising or complimenting TS, such as "TypeScript Makes You Never Want to Go Back to JavaScript", "TypeScript Sweet Series", and "If You Don't Embrace TypeScript, You're Getting Old!". According to the latest 2020 State of JS Survey Report, TypeScript's popularity and satisfaction are increasing year by year, with "TS fans" (developers who answered "would continue using" in State of JS) including this author, even exceeding 70% (as shown below).

In summary, TS now holds an unshakeable core position in the frontend field and is a very important frontend engineering development tool. TS is one of Microsoft's outstanding contributions to the software industry after embracing open source projects. However, TypeScript cannot improve the runtime efficiency of JavaScript code in browsers, nor can it increase developer productivity like React and Vue frontend frameworks, and it certainly cannot make your frontend pages look attractive. So what exactly makes it such a widely beloved "truly fragrant language"? What makes frontend developers love it so much? If you have similar questions, please continue reading. This article will explain in detail the advantages of using TS to develop large-scale frontend projects.

TS Introduction

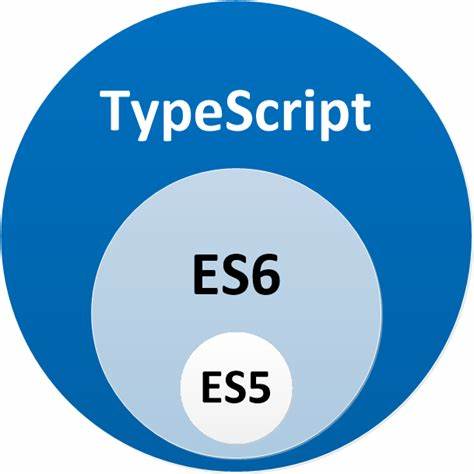

TypeScript was born at Microsoft and was designed and developed by Anders Hejlsberg, the chief architect of C# and creator of .NET. Simply put, TypeScript is JavaScript with a strong type system. It's a superset of JS, meaning TS supports all syntax in JS and extends many object-oriented programming (OOP) features. TypeScript's first public version 0.8 was released in October 2012 and received praise from GNOME founder Miguel de Icaza, though he pointed out that TypeScript's biggest drawback was its lack of mature IDE support—for example, at the time, only Visual Studio running on Windows could support TS, so Mac and Linux users couldn't effectively use TS to write projects. However, this drawback was quickly overcome. A year later, many editors, such as Eclipse, Sublime, and Vim, began supporting TypeScript syntax. Today, most mainstream editors can effectively support TypeScript. With TypeScript's support, you can enjoy TS-specific autocompletion and type hints in your IDE, making it easier to write reliable, high-quality code. As stated in the official website's one-sentence description of TypeScript: "Typed JavaScript at Any Scale."

Interface-Oriented Programming

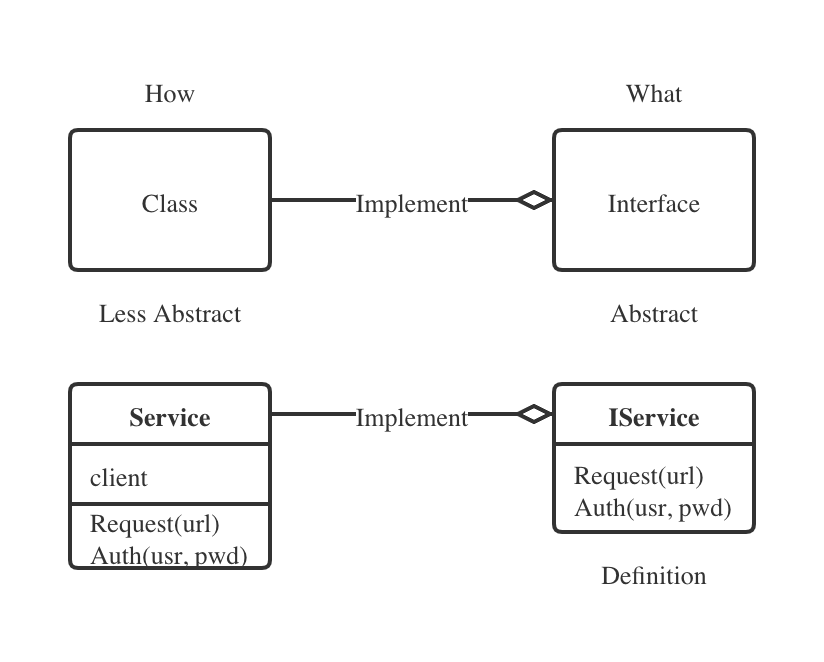

TypeScript's design philosophy comes from Interface-Oriented Programming (IOP), a programming design pattern based on abstract type constraints. To truly understand TypeScript, you must first understand the concepts and principles of interface-oriented programming. The paper "Interface-Oriented Programming" that initially introduced the IOP concept was published in 2004. It belongs to the object-oriented programming (OOP) system and is a more advanced and independent programming philosophy. As part of the OOP system, IOP emphasizes rules and constraints, as well as conventions for interface type methods, allowing developers to focus as much as possible on more abstract program logic rather than wasting time on more detailed implementation methods. Many large projects adopt the IOP programming pattern.

The above figure shows a diagram of the IOP programming pattern, which is commonly seen in OOP languages like Java or C#. Class methods are constrained by interfaces, and classes need to implement the abstract methods defined in interfaces. For example, the IService interface defines Request(url) and Auth(usr, pwd) methods. This interface doesn't care how these two methods are implemented; it only defines the method names, parameters, and return values. The specific implementation—the core code that realizes these functions—will be completed in the Service class.

This design pattern that emphasizes abstract method conventions has great advantages for building large projects. First, it doesn't require programmers to write any core code in the early stages of program development or system design, allowing programmers to focus their main energy on architectural design and business logic, avoiding wasting too much time thinking about specific implementations. Second, because IOP adds an abstraction layer of interfaces, it avoids exposing core code details to developers. Developers unfamiliar with a module can quickly infer program logic from documentation, names, parameters, and return values, greatly reducing program complexity and maintenance costs. Finally, IOP can make programming more flexible—it naturally supports polymorphism and can serve as an effective alternative to class inheritance in OOP. Many beginners might complain that this design philosophy makes programming bloated, but it must be said that this additional constraint can make large projects appear more stable and anti-fragile when facing complexity and variability.

Readers might ask, what does this have to do with TypeScript? Actually, if you've written large projects with TS, you should be able to realize the role that this IOP philosophy plays in TS. Next, this article will introduce some core concepts of TS, which will help readers further understand TS characteristics and why it's suitable for large projects.

TS Core Concepts

Basic Syntax

As mentioned before, TS is a superset of JS, meaning TS includes all JS syntax and adds a type system on top of it. Type definitions are mainly specified by adding a colon followed by the type after the variable or attribute name, i.e., <variable/attribute>: <type>. Below are examples using JavaScript and TypeScript code.

// JS

const strVal = 'string-value';

const objVal = {

key: 'string-value',

value: 1,

}

const func = param => param * 2;

The similar writing in TS is like this:

// TS

const strVal: string = 'string-value';

interface IObject {

key: string;

value: number;

}

const objVal: IObject = {

key: 'string-value',

value: 1,

};

type Func = (param: number) => number;

const func: Func = (param: number) => param * 2;

See the difference? First, you might notice that JS is much more concise than TS. This is natural because TS adds a type system, which inevitably increases some additional constraint code. JS is a weakly typed dynamic language where types can be freely converted, appearing very flexible. However, the coding pleasure from this flexibility and freedom can only last for a short time. When the project continues to develop, variable types increase, and inter-module interaction relationships become complex, the trouble brought by this freedom can be catastrophic. The common saying "dynamic programming is momentarily refreshing, refactoring is a crematorium" refers to this principle.

You might also notice that the object variable objVal is constrained by the interface IObject (defined using the interface keyword), which specifies the required properties and their corresponding types, so you can't handle assignment or value retrieval arbitrarily. Similarly, functions can also be defined using the type keyword, where the function type Func defines parameter names, parameter types, and return result types.

Basic Types

Like other mainstream programming languages, TypeScript also has basic data types. Most of them are consistent with JavaScript's basic data types, with some additional TS-specific types.

The list of basic types is as follows:

| Type Name | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Boolean | Boolean value | const a: boolean = true; |

| Number | Numeric value | const a: number = 1; |

| String | String | const a: string = 'text'; |

| Array | Array, variable length, same type | const a: string[] = ['a', 'b']; |

| Tuple | Tuple, fixed length, can be different types | const a: [string, number] = ['a', 1]; |

| Enum | Enumeration | Official example |

| Unknown | Uncertain | Official example |

| Any | Any type | Official example |

| Void | No type | Official example |

| Null and Undefined | Null values | Official example |

| Never | Used for functions that only throw errors | Official example |

| Object | Object, represents non-basic types | Official example |

Interfaces and Literal Types

In addition to basic types, TS also allows you to define custom types needed in projects. These custom types in TS are usually defined using interfaces or literal types.

Interfaces are a very important core concept in TypeScript. The definition method for interfaces is very simple—use the interface keyword plus the interface name in TS code, followed by curly braces {...}, and define the properties included in this interface and their corresponding types within the curly braces. These can be basic types, interfaces, classes, or types. Note that functions are also a type. Below is a code example:

interface Client {

host: string;

port?: string;

username?: string;

password?: string;

connect: () => void;

disconnect: () => void;

}

interface ResponseData {

code: number;

error?: string;

message: string;

data: any;

}

interface Service {

name?: string;

client: Client;

request: (url: string) => ResponseData;

}

Above is the interface definition code. Below shows how to use it:

const client: Client = {

host: 'localhost',

connect: () => {

console.log('connecting to remote server');

},

disconnect: () => {

console.log('disconnecting from remote server');

},

};

const service: Service = {

name: 'Mock Service',

client,

request: (url: string) => {

return {

code: 200,

message: 'success',

data: url,

},

},

};

This is a very simple code that simulates client service definition. You can notice that interfaces define the attributes (some articles call them "fields") and methods of the subsequent instances client and service. Instances under this interface constraint must contain the corresponding required properties and correct types, otherwise they will report errors at compile time. A question mark ? after a property name in an interface means that property is optional. Therefore, modules or functions are first defined by interfaces, and after considering the overall framework, the core logic in the interfaces is implemented. This satisfies the design pattern in interface-oriented programming.

Literal types are mainly used to simplify some relatively simple custom types. Their definition method is also very simple. Due to space limitations, I won't expand on this. Interested readers can go to the official documentation for in-depth understanding.

Duck Typing

After understanding basic types, interfaces, and literal types, we can start writing some reliable code with TS. However, to deepen our understanding of the TS type system, we need to understand under what circumstances the binding between interfaces and instances is legal. How are the type legality detection methods in TypeScript specified?

TypeScript adopts the so-called "Duck Typing" strategy. Duck typing means that when two types have the same properties and methods, they can be considered the same type. For example, dogs can eat and defecate, and have two eyes and one mouth; humans can also eat and defecate, and have two eyes and one mouth. From these properties alone, dogs and humans are the same type. But obviously, this conclusion is absurd. Humans can talk, but dogs cannot; dogs can wag their tails, but humans cannot. However, if an alien came to visit Earth, they might classify humans and dogs into one category because they can eat, defecate, and have two eyes and one mouth (误). However, through selective observation of two species, aliens can quickly classify them.

In fact, duck typing provides some flexibility while constraining types, making code flexible and concise without becoming bloated due to strict constraint conditions. TypeScript uses this method to verify type legality, which can improve the experience of writing TS, bypassing the rigid type constraints of traditional OOP languages (such as Java, C#), making writing TS relaxed and interesting.

Others

Due to space limitations, this article doesn't plan to detail all TS features. However, TS has many other practical features, such as union types, enums, generics, namespaces, etc. Readers who want to further understand or use TS can go to the official documentation for in-depth study.

Building Large Projects with TS

What do you first think of regarding large projects? For development engineers in different fields, there might be different understandings. However, from the software industry perspective, a software development project being called a "large project" usually means it will involve a large number of functional modules, thus having high system complexity. The success of a large project, in addition to meeting traditional project management requirements like schedule and budget control, also needs to focus on quality—from a software engineering perspective, this means robustness, stability, maintainability, scalability, etc. Just like construction engineering, you definitely don't want the building you design to be shaky; you need it to be as stable as possible, standing firm in storms while being flexibly maintainable. To ensure these non-functional requirements or quality requirements, there must be clear specifications and standards. In construction engineering, these might be engineering drawings and precise measurements, while in software engineering, they are coding standards, design patterns, process standards, system architecture, unit testing, etc. Among these, coding standards and design patterns are particularly important because they are the foundation of the entire software system. Without code, there will be no software programs; without good coding standards and design patterns, there will be no good code, and thus no reliable software programs—only endless program bugs and system crashes. TypeScript can greatly improve code quality in terms of coding standards and design patterns, thereby enhancing system robustness, stability, and maintainability.

Code Standards

Code style is often a pain point in frontend projects, which can be standardized using the JavaScript style detection tool ESLint. However, ESLint cannot solve problems caused by types. Only TypeScript can statically detect possible problems at the type level. If you use TS to write frontend projects, I recommend constraining all possible variables and methods with types. Moreover, try not to use the any type because any can cover all other types, which is equivalent to having no type, defeating the purpose of the type system.

Compared to pure JS, although TS has some additional type declaration code, it gains better readability, understandability, and predictability, making it more stable and reliable. If you're a beginner transitioning from JS to TS, please try to resist the urge not to use any—this will ruin your standards and specifications. If you're using a frontend-backend separation architecture and writing frontend in pure JS, without clear and reliable backend interface data structure agreements, you might be forced to write a lot of type judgment code, which pollutes the entire code style like using reflection in static languages.

TS is essentially JS with an additional static type system—there's no other magic. But this "small" additional feature makes code standardized and maintainable, making it the preferred choice for large frontend projects. Many senior frontend engineers like to use React or Angular to build large projects precisely because they support TS. However, the recently released Vue 3 has also timely added TS support, enabling it to handle large project development.

Directory Structure

When writing large frontend projects, I recommend using declaration files to manage interfaces or other custom types. Declaration files are generally in the form of <module_name>.d.ts, where only module types are defined without any actual implementation logic. Declaration files can be placed in a separate directory—I like to name it interfaces, meaning interfaces. This way, abstract types, methods, properties, etc., can be fully separated from actual content.

The following example is a Vue project directory that integrates TS:

.

├── babel.config.js // Babel compilation configuration file

├── jest.config.ts // Unit test configuration file

├── package.json // Project configuration file

├── public // Public resources

├── src // Source code directory

│ ├── App.vue // Main application

│ ├── assets // Static resources

│ ├── components // Components

│ ├── constants // Constants

│ ├── i18n // Internationalization

│ ├── interfaces // Declaration file directory

│ │ ├── components // Component declarations

│ │ ├── index.d.ts // Main declaration

│ │ ├── layout // Layout declarations

│ │ ├── store // State management declarations

│ │ └── views // Page declarations

│ ├── layouts // Layout

│ ├── main.ts // Main entry

│ ├── router // Router

│ ├── shims-vue.d.ts // Vue compatibility declaration file

│ ├── store // State management

│ ├── styles // CSS/SCSS styles

│ ├── test // Tests

│ ├── utils // Common methods

│ └── views // Pages

└── tsconfig.json // TS configuration file

As you can see, the interfaces directory is at the same level as other modules, and its subdirectories correspond to type declarations for other modules. Before writing code, try to create and design declaration file content first, then go to actual modules to complete implementation after design. Of course, this "definition → implementation" is an iterative process. You might discover type design problems during implementation and can return to declaration files to improve definitions, then optimize implementation code.

Design Patterns

Before ES6 came out, JavaScript's type system was quite difficult to understand, mainly because of its hard-to-master prototype inheritance pattern. Before ES6, implementing a factory method from traditional OOP was quite challenging. However, ES6's appearance alleviated frontend engineers' pain points. ES6 introduced class syntax sugar to implement traditional OOP class creation and inheritance. However, from TypeScript's perspective, this is just "minor tinkering." Although class in ES6 gives JS some encapsulation capabilities, it still seems inadequate when building large projects or system modules. The lack of a type system, especially generics, is a fatal weakness of JS. TS not only has all the functionality of class in ES6 but also has interfaces, generics, decorators, and other features to implement various flexible and powerful framework-level systems. Generics are usually an essential feature of framework libraries—they can make a class or method more universal. I recommend extensively using features like interfaces and generics in large projects to abstract your code and logic, thereby extracting repetitive code and optimizing the project overall.

How to Learn TS

The main purpose of this article is to encourage developers to use TypeScript to build large frontend projects, not to serve as a reference guide. Therefore, this article won't detail how to create TS projects from scratch or how to use various TS features to write code. Readers interested in in-depth study of TS after reading this article need to read more TS reference articles for deeper understanding.

For beginners, this article will provide some ways to help you quickly master TS.

Official Documentation

Official documentation is the most authoritative reference guide. Starting directly from official documentation is the most systematic and effective learning approach.

- Carefully read the TypeScript Official Documentation, including Get Started, Hand Book, Tutorials, etc.

- If you're not comfortable reading English documentation, you can check the TypeScript Chinese Website for documentation.

Technical Articles

TS has been developing for many years, and there are already numerous technical articles about TS online. Here are some helpful blog articles:

- TypeScript Best Practices

- A Rare TS Learning Guide

- Learning TypeScript with Examples

- 50 Rules and Experiences for React + TypeScript You Might Need

Practical Projects

"Practice makes perfect." In the learning process, theory and practice are always inseparable. If you can apply learned knowledge to actual projects, it will not only deepen your impression but also let you personally experience the benefits brought by new technologies and their existing shortcomings. You can try the following practical project approaches:

- Create a TypeScript project from scratch using scaffolding tools like Vue CLI, create-react-app, etc.

- Study mature TS projects like Ant Design, Nest, Angular, etc., to understand how declaration files are organized.

- Study the open source project DefinitelyTyped to understand and practice how to make old JS projects support TS.

Conclusion

Embracing TypeScript is the mainstream of modern frontend engineering. Every frontend engineer needs to learn TS, which helps broaden your knowledge and skills and strengthen your professionalism and career background. However, we must realize that embracing TS is not the endpoint. If you've studied the history of frontend development, you'll find that TypeScript's popularity is the result of frontend engineering, modularization, and scaling—it's an inevitable product of increasingly complex frontend requirements. TS is just an effective solution using backend engineering knowledge to solve frontend engineering problems. The TypeScript creator cleverly transplanted C# experience to JavaScript, giving birth to TypeScript, revolutionarily liberating frontend engineers' productivity. How long this solution will last, we cannot predict. But what's certain is that frontend engineering will continue to develop, and various new technologies will emerge endlessly. As a software engineer, you need to keep learning so you won't be knocked down by the next wave.